In this bi-weekly series reviewing classic science fiction and fantasy books, Alan Brown looks at the front lines and frontiers of the field; books about soldiers and spacers, scientists and engineers, explorers and adventurers. Stories full of what Shakespeare used to refer to as “alarums and excursions”: battles, chases, clashes, and the stuff of excitement.

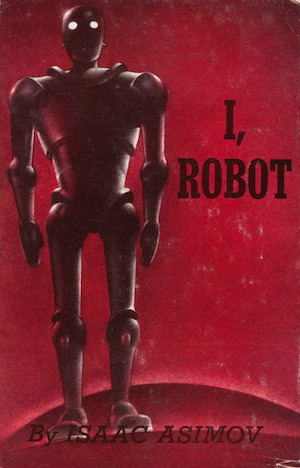

Today, I’m revisiting a classic collection of tales from one of the giants of the science fiction field, Isaac Asimov. As a writer, Asimov loved coming up with a good puzzle or conundrum that required a solution, and some of his best known works address the creation of machines whose operation was guided by logic. Despite their logical nature, however, the robots in the stories included in I, Robot prove to be just as unpredictable as humans, giving the characters plenty of mysteries to grapple with

As I recollect, my first science fiction convention was a WorldCon in Baltimore back in the 1980s. My dad had been attending conventions for years, so he was my guide to this new world. He insisted I attend a panel hosted by Gay Haldeman and the late Rusty Hevelin on how to enjoy a convention, which was a great start. Then he took me to a big ballroom full of tables, mostly empty or swathed in white clothes. There were boxes and boxes of books and all sorts of trinkets being brought into what my dad called the “huckster room.” And then dad got all excited, and started to hurry me across the ballroom. “Hey, Ike!” he called out to another grey-haired man across the room. The man turned, I saw those huge, distinctive sideburns, and I realized “Ike” was Isaac Asimov, one of the giants of the science fiction field.

Asimov, along with Arthur C. Clarke and Robert A Heinlein, was considered one of the Big Three, authors whose works defined the science fiction genre. I noticed Asimov peek at my dad’s nametag, so dad clearly knew him more than he knew dad, but he was affable and generous with us. I think I actually stammered out a fairly coherent, “An honor to meet you, sir;” my only contribution to the conversation. My dad told me later that not only had they met a few times at science fiction events before, but he had been a patron at the Asimov family’s candy store, and been waited on by Asimov when they were youngsters. He took great pleasure in knowing such a talented author. And over the years, I developed a great deal of respect for Asimov, his work, and his influence on the field.

But despite my respect for Asimov, I must admit it’s taken me a while to review his work. The only book by Asimov I had in my collection was an omnibus edition of the Foundation Trilogy. When I’d read that in my youth, I hadn’t been impressed: I appreciated the way the narrative grappled with the grand sweep of history, but instead of showing pivotal events, the series was full of scenes where characters simply talked about the events. And the series looked at history as being resistant to the impact of individual heroism, rather than being shaped by it—an idea that didn’t sit well with me. So over the years, I’ve been keeping my eye open for other works by Asimov. I did enjoy many of his short stories, appreciated his knack for selecting great stories for anthologies, and adored his non-fiction science writing (which not only made me smarter, but was so clearly written, it made me feel smarter).

Finally, a few weeks ago, I was in my favorite used bookstore, and saw I, Robot on the shelf—a later edition which featured a picture from the 2004 Will Smith movie (a film almost totally unrelated to Asimov’s work, but that’s another story). As I flipped through it, I realized I had found the perfect book to feature in this column.

About the Author

Isaac Asimov (1920-1992) was a prolific American writer, who while known for his science fiction, also wrote and edited books encompassing (but not limited to) science fact, fantasy, history, mysteries, and literary criticism. Altogether, his name has appeared on over five hundred books.

Asimov was born in Russia, and was brought to America by his parents when he was three. The family settled in Brooklyn, New York and operated a succession of candy stores, and Asimov credited the magazines sold in the store with igniting his love of literature. Asimov’s father was suspicious of the quality of these magazines, but Asimov managed to convince him that the science fiction magazines, with “science” in their titles, were educational.

Asimov was educated in chemistry, receiving a BS in 1939, and an MS in 1941. During World War II, he worked at the Philadelphia Navy Yard alongside fellow science fiction luminaries Robert Heinlein and L. Sprague DeCamp. In a strange bureaucratic quirk, he was then pulled from this job and drafted into the Army as a private, an action that no doubt hurt the military more than it helped. He reached the rank of corporal, and his short service came to an honorable end shortly after the war was over. He then continued his education, obtaining a PhD in 1948.

Asimov’s first science fiction story appeared in 1939, and he developed a friendship with Astounding/Analog editor John Campbell, who published many of Asimov’s early works. It was in the 1940s that he produced his most seminal science fiction tales, including the classic story “Nightfall,” the stories later collected in I, Robot, and those included in the Foundation Trilogy.

Toward the end of the 1950s, Asimov began to focus more on science writing and non-fiction, including a long-running science column in the Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction. Asimov and Arthur C. Clarke developed a friendly agreement where Asimov would tell people Clarke was the world’s best science fiction writer if Clarke would call Asimov the world’s best science writer. Later in Asimov’s career, he turned back to writing science fiction, producing books that tied together his previously separate Robot and Foundation series. And in 1977, he started Isaac Asimov’s Science Fiction Magazine, a magazine that has survived to this day and still bears his name.

Asimov’s career and contributions have been recognized with a whole host of awards, including a number of Hugo and Nebula Awards, his selection as a SFWA Grand Master, and his induction into the Science Fiction and Fantasy Hall of Fame. I can’t possibly do justice to Asimov’s life, influence, accomplishments, and awards in this relatively short biographical summary, so I will point those who want to learn more to his extensive entry in Wikipedia, his entry in the Encyclopedia of Science Fiction, and his entry in the Encyclopedia Britannica.

You can find a few of Asimov’s non-fiction works on Project Gutenberg, but none of his fiction, the rights to which are quite valuable, and thus not likely to fall into the public domain anytime soon.

Real-Life Robots Versus Asimov’s Robots

Asimov, as was the case with many authors of his time, encountered difficulties when trying to predict the future of computing, although there were many things he got right. His fictional term “robotics” entered the lexicon in the real world, and now describes a whole field of scientific development. He imagined robots as a kind of artificial human. His fictional “positronic” brains function in a manner similar to human brains, allowing the robots to learn and adapt their behavior over time. His robots also learn by reading books. In the real world, computing power has expanded and evolved rapidly, but we are still a long way from electronic brains that function like a human brain.

Robots in the real world also do not look like humans (at least not yet). Robots instead lurk inside more familiar objects—they are built into our cars and our appliances. They allow tools like lathes and 3D printers to be quickly and easily reprogrammed to build different objects. You do encounter robots in factories and warehouses, but if they are mobile at all, they tend to look more like a forklift than a person. Only when you see mechanical arms in operation do you get a hint of similarity to a human or living creature. Robots remain specialized, designed and shaped to perform very specific tasks.

Asimov did anticipate the challenges of programming machines to perform tasks, and his musings on the laws of robotics represent an early attempt to grapple with the challenges of computer programming. Because they are so central to the stories being discussed below, I will transcribe those laws here:

First Law: A robot may not injure a human being or, through inaction, allow a human being to come to harm.

Second Law: A robot must obey the orders given it by human beings except where such orders would conflict with the First Law.

Third Law: A robot must protect its own existence as long as such protection does not conflict with the First or Second Law.

The laws were modified somewhat over the years and Asimov later added what he referred to as the “Zeroth Law”—a robot may not harm humanity, or, by inaction, allow humanity to come to harm.

While the readers of the time the robot stories were written could approach them without preconceived notions, readers of today will have to set aside their knowledge of current robotics in order to enjoy them. As with many stories written in the 20th century, the tales in this book have passed into the category of alternate history.

I, Robot

Like many early books by science fiction writers from the era, I, Robot is a fix-up, a collection of short stories written between 1940 and 1950 knitted together by framing material. The format of linked stories works to Asimov’s strengths as a short story writer, and makes for an entertaining read. In this case, the frame is provided by a journalist interviewing the famous roboticist Susan Calvin about her career, which began when she was twenty-six, in the year 2008. While a strong female character like Ms. Calvin was a rarity in the science fiction of the 1940s, Asimov does not always present her in the most favorable light, frequently describing her as cold and emotionless.

“Robbie” is the first robot story Asimov ever wrote. Calvin tells the tale as one she heard from before her time with U.S. Robot and Mechanical Men, Inc. Robbie was one of the first robots commercially produced, unable to speak, but programmed to be a companion for a little girl named Gloria (I found this somewhat unconvincing, as the behaviors and abilities Robbie does exhibit seem more complex than simple speech would require). But the mother faces peer pressure from other wives who are suspicious of technology, and convinces her husband to replace Robbie with a dog. Little Gloria is inconsolable, and dad (without consulting mom) cooks up a scheme for her to “accidentally” meet Robbie again during a factory tour. Factories can be dangerous, but Robbie is loyal and competent, saves the day, and everyone lives happily ever after.

“Runaround” introduces robot troubleshooters Gregory Powell and Michael Donovan. Robots are mistrusted and restricted on Earth, but by the early years of the 21st century, humankind has spread into the solar system, and robots make excellent miners in the harsh conditions of other planets. Greg and Mike are the kind of characters I call “chew toys,” tossed by authors into a story the way I toss Lambchop dolls to my dog, with their trials and tribulations becoming the driving force for the narrative. The duo is on Mercury, where robots have been acting up. The robots are uncomfortable working without human supervision, and Greg and Mike end up risking their lives on the surface. Their situation becomes so dire that the First Law overrides other programming, and the robots finally fall into line.

To escape the heat, Greg and Mike volunteer to work further from the sun, but in “Reason,” a stint in the asteroids makes them miss the warmth. A new robot, QT-1, whose nickname is Cutie, has been doing some reading and thinking for himself, with disastrous results. He has decided that humans are inferior beings, and it takes some clever thinking to get Cutie to perform his assigned tasks of processing and delivering the asteroid mine’s ores. Their solution is far from perfect, but it works.

The story “Catch That Rabbit” has Greg and Mike trying to figure out why a new type of multiple robot, designed to work in gangs, only does the job when supervised by humans. The senior robot, DV-5 or Dave, can’t explain exactly why he keeps failing at his duties, so it is up to our intrepid troubleshooters to get to the bottom of things.

“Liar!” finally brings Susan Calvin to the center stage, dealing with the accidental development of a mind-reading robot. The story first appeared in Astounding, and in that era, editor John Campbell was fixated on the concept of advanced mental powers. While robots are generally honest, this one begins telling different stories to different people, driven by its knowledge of their often-hidden desires and by its First Law compulsion to protect them from harm.

“Little Lost Robot” brings Susan Calvin out to the asteroids, where humanity is working on interstellar spacecraft. The work is so hazardous at the Hyper Base that some robots have been reprogrammed with a relaxed First Law to prevent them from interfering with the dangerous work. Now one of those reprogrammed robots is hiding among its more traditionally programmed counterparts. If they can’t find the renegade robot, they will have to destroy all the robots on the base…an embarrassing and costly setback. This story presents Susan at the height of her abilities, running circles around the baffled men who surround her.

“Escape!” features a thinking robot called the Brain, who has the intellect to help humanity solve the problem of hyperatomic travel and make interstellar travel possible. The problem has apparently destroyed the mind of an advanced robot from their competitors, Consolidated Robots, and they risk their own advanced Brain by applying it to the same issue. But after some careful guidance from Susan Calvin, the Brain offers to build an experimental ship without human intervention. The ship is finished, and our hapless troubleshooters Greg and Mike return to center stage to inspect it, only to find themselves whisked away into the depths of outer space aboard the mysterious and uncommunicative spacecraft. Robots may be programmed not to harm humans, but the Brain seems to have a flexible interpretation of what that means.

“Evidence” gives us a politician, Stephen Byerly, who is running for office, but has been accused of being a robot. Then he punches an obnoxious man at a rally, convincing everyone that, because of the First Law, he can’t be a robot after all. But Susan Calvin finds that the obnoxious man was a robot himself, which is why Byerly could attack him; the robotic imposter goes on to a distinguished political career.

“The Evitable Conflict” brings Susan Calvin back in contact with Stephen Byerly, the humanoid robot from the previous story. He has ascended to leadership of world government (Asimov predicts, overoptimistically, that after the World Wars of the 20th century, humanity would at last come to its senses). Byerly is seeking Susan’s advice, troubled by a rash of incidents that are preventing the economy from operating at peak efficiency—something that should be impossible now that a great Machine is calculating the best courses of action. This story hints at Asimov’s later works, where he merged the psychohistory of his Foundation stories with his Robot series.

Final Thoughts

I, Robot is a bit dated, having been overtaken by history, and portrays technologies that have developed quite differently in the real world. But the puzzles it poses are entertaining, and it is a pleasant change of pace to read stories where (other than a single punch in the nose) no one solves problems with violence. These stories represent Asimov’s work at its best, and I enjoyed revisiting them.

And now I look forward to your comments. If you’ve read I, Robot, or Asimov’s other robot tales, I’d love to hear your thoughts. And which of his other works might you want to see me take a look at in the future?

Alan Brown has been a science fiction fan for over five decades, especially fiction that deals with science, military matters, exploration and adventure.